Sign up for the One Day In July newsletter to receive meaningful musings and investor insights from founder and CEO Dan Cunningham. Once a month, direct to your inbox.

I know, I know. You're heading to the beach this weekend and you want pictures, not words. You can't see all those words on a screen in the bright sunlight, and anyway it's summer.

Before I dive into a visual festival of charts, I want you to keep in mind the risk of fitting the story to the data you are looking at. It is very easy these days, in finance (or politics) to believe something, and then just find some data that matches that belief.

In his 2012 annual letter, Buffett wrote about this problem:

I ask the managers of our subsidiaries to unendingly focus on moat-widening opportunities, and they find many that make economic sense. But sometimes our managers misfire. The usual cause of failure is that they start with the answer they want and then work backwards to find a supporting rationale. Of course, the process is subconscious; that is what makes it so dangerous.

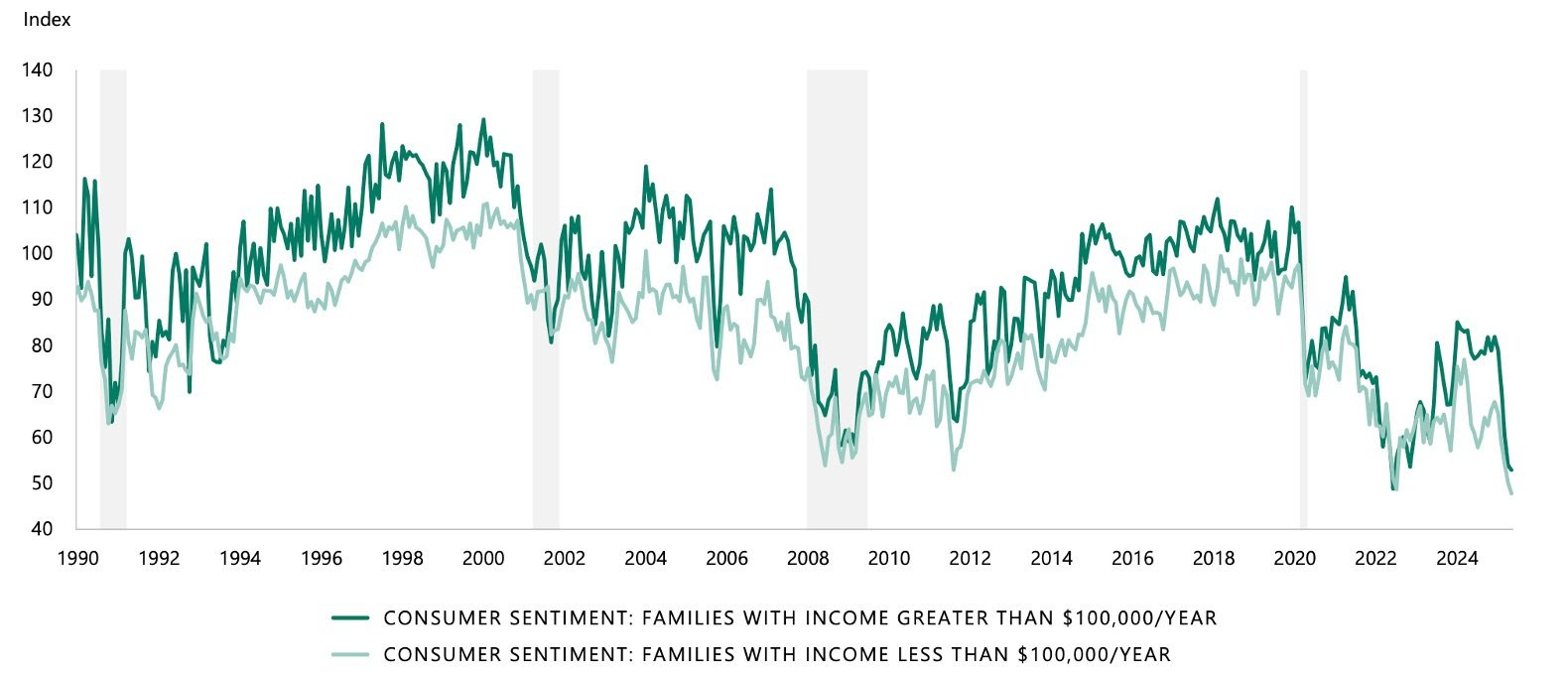

Let's get the negative out of the way. People are in a terrible mood, with consumer confidence hitting it's lowest level in 35 years (including the Global Financial Crisis) across income groups both below and above $100k:

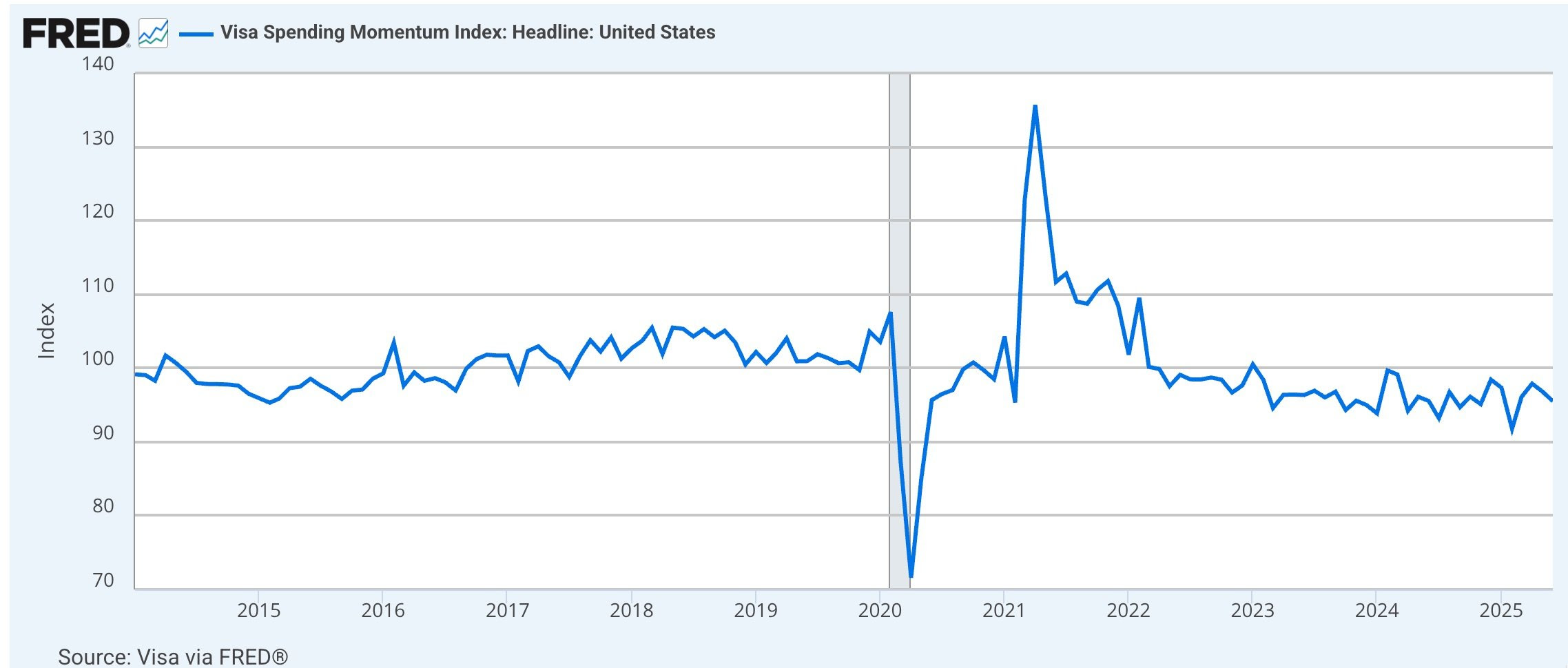

This is spending momentum, from VISA. Below 100 on the chart means spending momentum is below its long-term average rate.

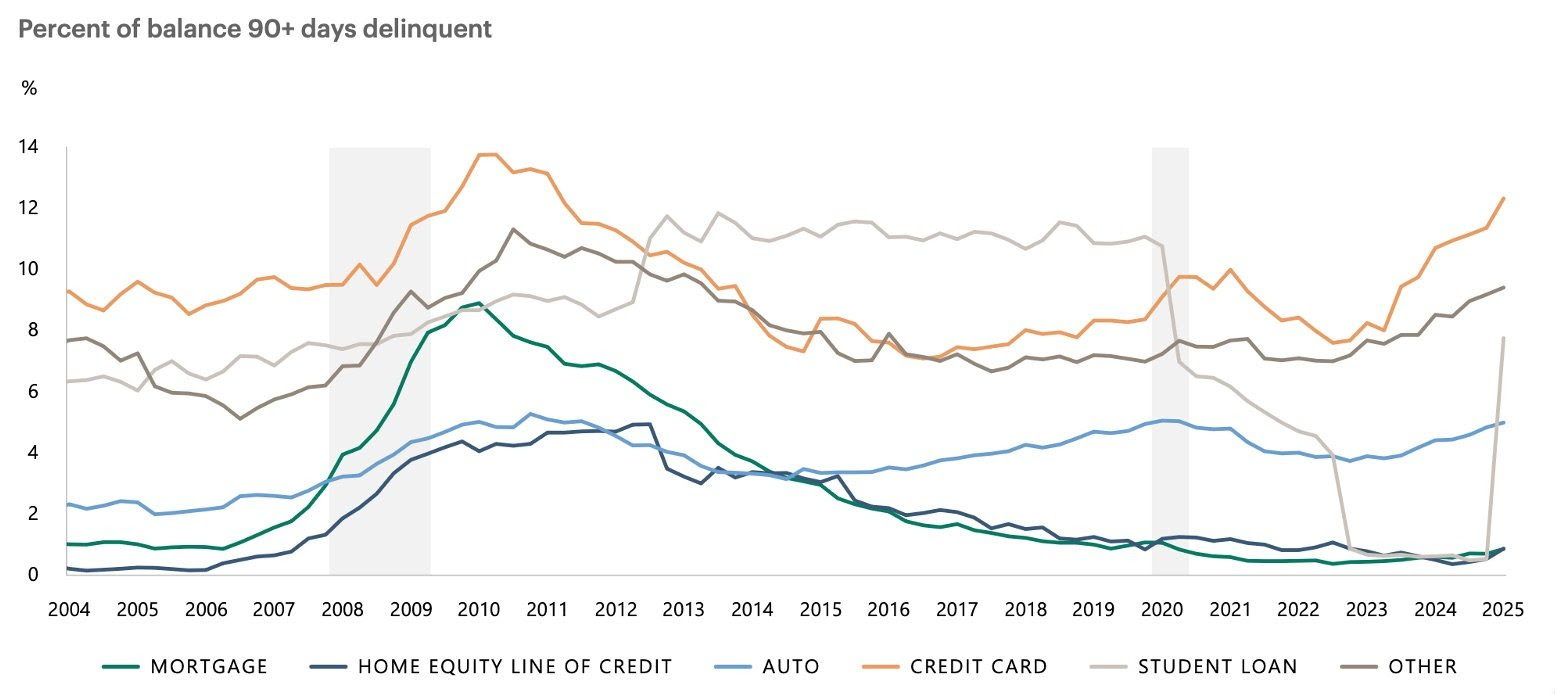

But the spending isn't always paid for. Here is a chart of debt types, more than 90 days delinquent. Note the surge in credit card debt not being paid, as well as student loans:

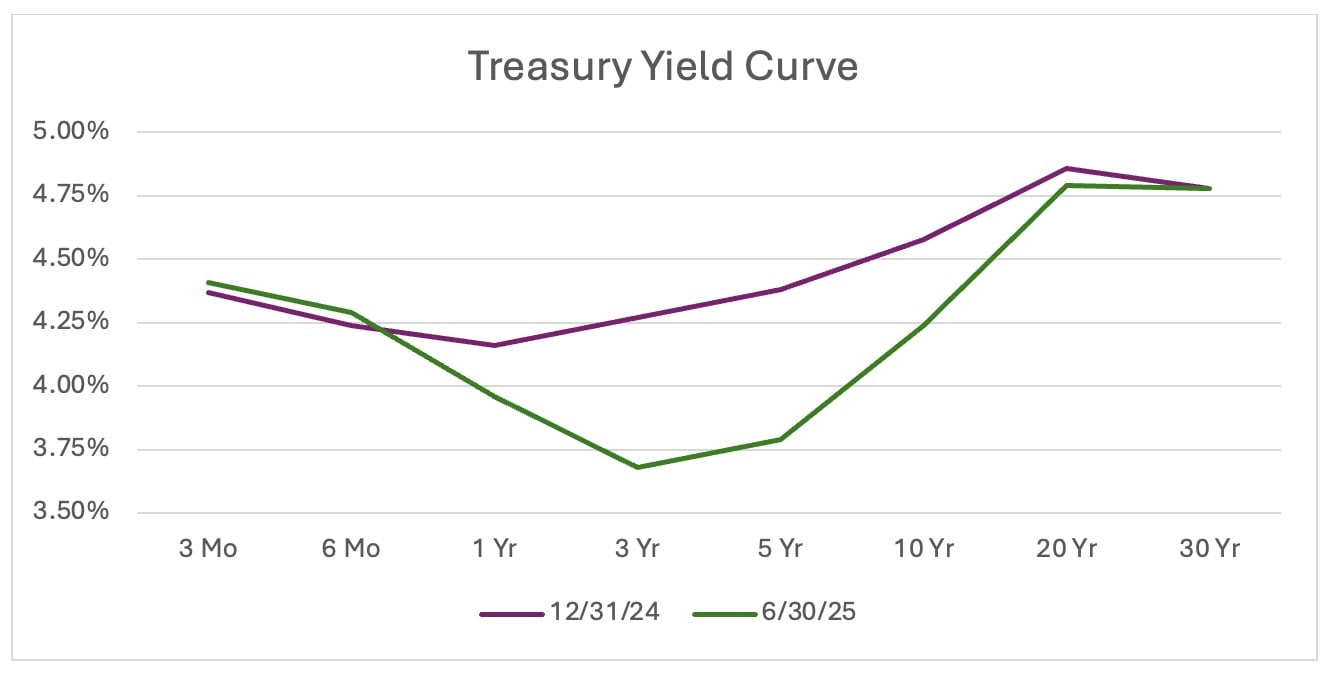

Onto rates. We have a "positive butterfly twist" yield curve. (Throw that term out at tonight's lobster bake on the beach.) The green line is as of June 30th. The dip in the three-five-year yield shows that investors expect rate cuts in the relatively near future. They are buying in the three to five year range to lock in rates, without exposing themselves fully to the duration risk further out the curve.

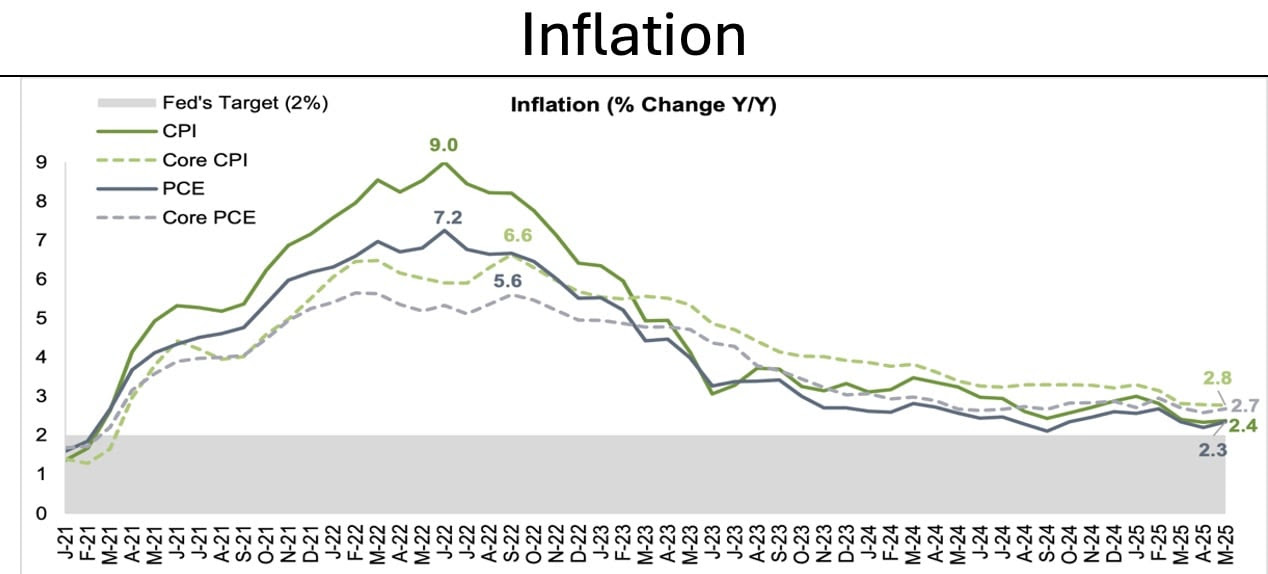

Inflation is not back to the Fed's 2% target yet, adding some uncertainty to the rate cut debate:

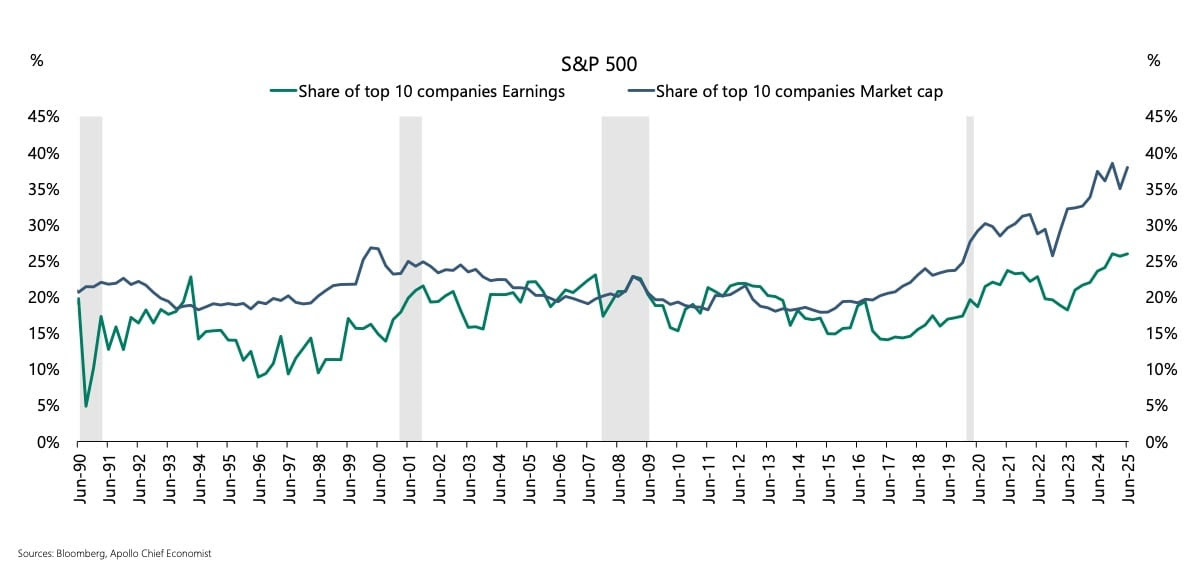

In the S&P 500, concentration is the highest it has been in 35 years. Note that the market is not necessarily wrong. The "Magnificent 7" tech firms have done a magnificent job creating high-growth monopolies for themselves that are difficult for competitors to attack, and the market reflects this. Profits are not quite as dominant as index share, primarily due to: 1. Spending on AI infrastructure is suppressing profits in the Magnificent 7 and, 2. The price-earnings ratio of the Magnificent 7 as a group is higher than that of the S&P 500. (For more reading on this, here is a 2023 newsletter I wrote.)

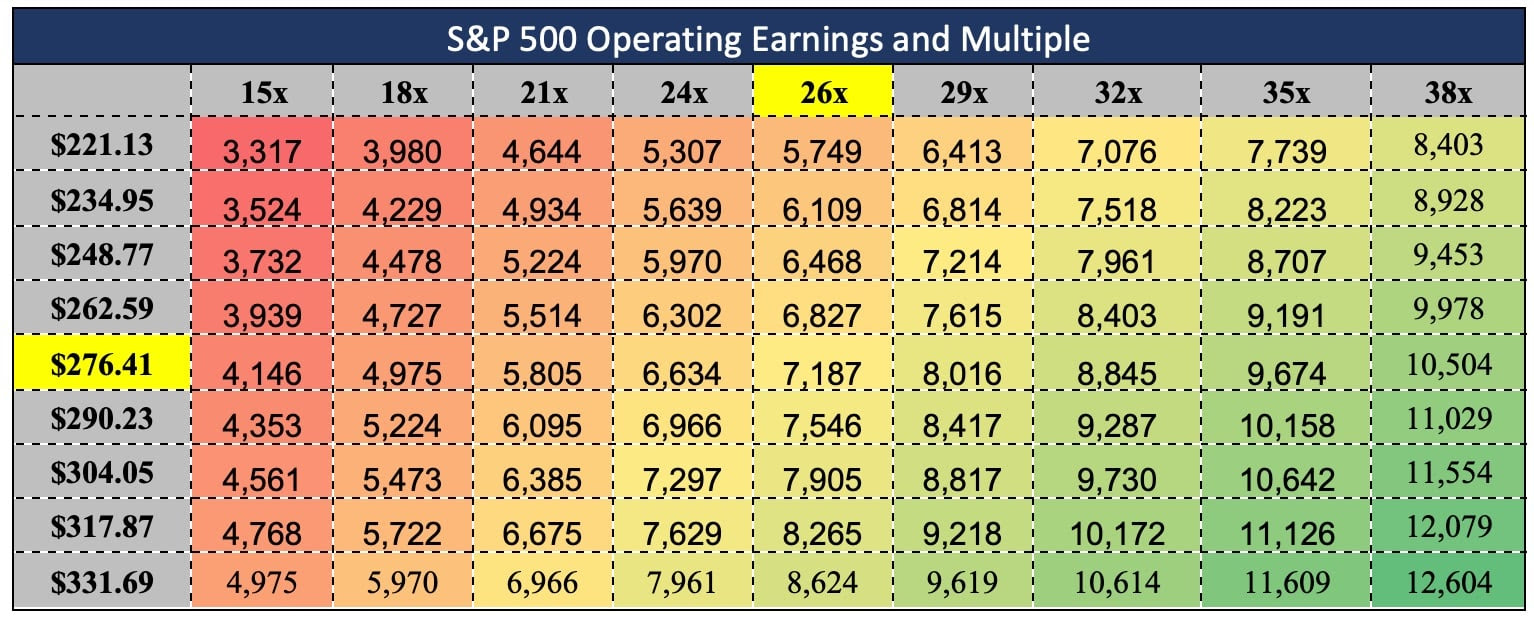

Ok, last chart. Here are the potential operating earnings of the S&P 500 for 2025 (y-axis) and the potential price-earnings trailing multiple (x-axis). Currently analysts expect 2025 earnings in the $260 to $270 range, and the current trailing multiple is about 26. Today the S&P trades at $6,307. You can play some visual checkers on this chart to see how a change in either the earnings or the multiple will affect the price of the S&P 500.

Ok that was a lot to absorb! Have a nice, hot weekend!

Dan Cunningham

Graph Sources:

1. Consumer Sentiment: Apollo Mid-Year Outlook 2025.

2. VISA Momentum: Visa via FRED.

3. Credit cards delinquent: Apollo Mid-Year Outlook 2025.

4. Treasury Yield: U.S. Treasury

5. Inflation: Sifma U.s. Economic Survey Mid-Year 2025.

6. Concentration: Apollo.com June 2025

7. S&P Operating Earnings and Multiple: S&P Global

Before we get to the main event, I wanted to point out this nugget that showed up in the Wall Street Journal yesterday: more than 8 in 10 investment advisors are now outsourcing investment decisions for at least some of client assets.1 This seems odd to me, that the core purpose of an investment firm is now being outsourced to someone else.

This brings up an interesting thought though, as One Day In July favors passive indexed investments. Somewhere in the investing process, there are active decisions made, always. It's just a matter of at which level in the investing stack the decision becomes active. We feel like an optimal approach is at the fund level. This allows us to garner the performance and low costs of passive investing while maximizing diversification, risk reduction, and customization.

Before we get to the bond market, I want to discuss how information enters One Day In July. Many of you have asked about this. Let's look at the media business: there are three reliable ways to make money in the media industry. 1. Be named Google or Facebook, and either scrape the Internet to get free seed content or get your users to do it for you, aggregate that content, and sell ads on it. 2. Play to already-established political partisanship of your readership and use ads or get paid a relatively low monthly fee so users can keep seeing/reading things they already believe or 3. Be in financial media and get paid a premium subscription rate because subscribers need to know what is happening to make decisions.

These have been pretty good business models, especially #1. We have used #3 in the form of Bloomberg and Wall St Journal subscriptions (in addition to other sources, generally individuals or analysts posting on their own). Both firms clearly break out news from opinion (one tilts left, one right on the opinion side) and are considered reliable sources. But financial news headlines, even a bit in these publications, seem to be increasingly sensationalized.

The Treasury market is a good example. Many headlines this year implied doom was at hand. But if you look at the actual data, that's not the case. Here is Treasury auction demand from the spring of 1999 to the spring of 2025 on the 10-Year Treasury note:

The vertical lines on this graph show the size of the auction, defined by the numbers on the right side of the graph, and the squiggly line is the bid-to-cover ratio, defined by the numbers on the left side of the graph. The bid-to-cover ratio is the total of number of bids received divided by the total number of securities sold. Notice that recent demand for Treasuries has been rising, even on substantially bigger debt offerings! And that story all over the Internet about foreign buyers abandoning Treasuries? Well, a tiny bit, but not in any material way. Demand was over 65% from foreign investors, up 6% from May, and around the one-year average. Though about 2% below the long-term average of 67% foreign demand.

This doesn't mean there are not structural long-term risks in the U.S. government's balance sheet. But in the near term, with over 2.5 buyers for every bond being offered, we are not seeing either domestic or foreign appetite wane.

Dan Cunningham

1. More Financial Advisors are Outsourcing Investment Decisions - WSJ - 6/12/25

2. Graph & Demand Data: U.S. Treasury

Journalist David Brooks wrote this last year:

The bottom line is that if you give somebody a standardized test when they are 13 or 18, you will learn something important about them, but not necessarily whether they will flourish in life, nor necessarily whether they will contribute usefully to society’s greater good. Intelligence is not the same as effectiveness. The cognitive psychologist Keith E. Stanovich coined the term dysrationalia in part to describe the phenomenon of smart people making dumb or irrational decisions. Being smart doesn’t mean that you’re willing to try on alternative viewpoints, or that you’re comfortable with uncertainty, or that you can recognize your own mistakes. It doesn’t mean you have insight into your own biases. In fact, one thing that high-IQ people might genuinely be better at than other people is convincing themselves that their own false views are true.

This is a significant problem in the investment world. Many of the decision-makers in investing checked all those high-IQ boxes, are stamped with fancy degrees, and have had continuous signal bestowed upon them that their insights carry extra weight. This becomes dangerous because the market is a playing field that does not care about those things - it puts no value on who the investor is. In that regard it is truly democratic. A good investor must always be careful to invert the question and argue the other side of the trade.

It's probably fair to say that people who are considered classically intelligent are good at creating complex systems. This reflects in investing because one of the most profitable things firms can do is obscure the fee structure for clients, and there are many ways to accomplish this (scroll down here to see our list). After a short period of self-justification, the fee-obscurers high-five and some people fist bump and then there is that awkward post-Covid-era confusion about whether you are high-fiving or fist bumping, but regardless everyone thinks about how much cash flow they created for the firm, and then some people probably even take the afternoon off, thinking "Today was a biggie, I can accomplish no more."

This is obviously bad because these fee complexities are difficult for the investor to unwind, and they prey on people's time. The fact is that almost everyone who is not paid to create these structures has trouble seeing through them. My father-in-law used to joke that we all need to "eschew obfuscation."

We are hired by people to see through these things, and there are times when we struggle. So don't feel bad.

Here's the conundrum, and I think about this a lot. The obscurity above is bad. But is all obscurity in investing so evil? Day-trading apps hide how they make money, and that isn't going to win them any ethics prizes, but the information on investing is almost real-time in your hand. It's much clearer than illiquid investments that do not trade in a market. But maybe in a lot of cases obscurity brings a lack of knowledge, and an implicit friction to get that knowledge, that has value. In other words, it's better not to always know what is going on.

Over time I have come to see this as a big value-add area for One Day In July. As a client it's better not to track what is happening at every moment, because it helps you to psychologically weather storms and euphorias. This will likely increase your financial returns at the same time as it decreases your blood pressure. You want some friction if you go to buy or sell based on emotion. If you are one of our clients, you know your advisor is going to want to talk about this buying high or selling low, and maybe that's enough to say "Okay, you know, forget it. Let's stay with the plan and I'm going back to work on my garden, where my tulips came up in colors that don't match last fall's packaging."

Ideally, you want clear information on certain things, like fees and prices and potential conflicts of interest. But if the market gets too clear and friction-free, you might get yourself into trouble.

Dan Cunningham

1. The David Brooks quote was in The Atlantic, December 2024.

2. Matt Levine at Bloomberg and Cliff Asness at AQR have written about investment obscurity here and here.