March 10, 2017

On point today is the idea of optimism in investing, and not timing the markets. My depressing talk of mushroom clouds on the horizon in the last newsletter perhaps gave the wrong message. Since 1776, betting against the United States, or any country that embraces free-market capitalism, has been a terrible error. For example, during the 20th century the Dow advanced from 66 to 11,497, or a 17,320% gain, and that did not include the 45% of returns, per year, attributed to dividends.

Yet...

"For reasons I have never understood, people like to hear that the world is going to hell," historian Deirde McCloseky told the New York Times in January 2016. And "Despite the record of things getting better for most people most of the time, pessimism isn't just more common than optimism, it also sounds smarter. It's intellectually captivating, and paid more attention to than the optimist who is often viewed as an oblivious sucker," Morgan Housel.1 People don't perceive market cheerleaders to be particularly bright.

Here in Vermont, in the crash of 2008-2009, the Burlington Free Press put the news on the front page six times. In the massive recovery that followed, I have not seen it mentioned once. An investor lost *far* more money being out of the market than lost riding the crash all the way down.

And today, bloggers and prognosticators, when they can catch their breath from selling their books and subscriptions, are hugely pessimistic.

So how is that working out?

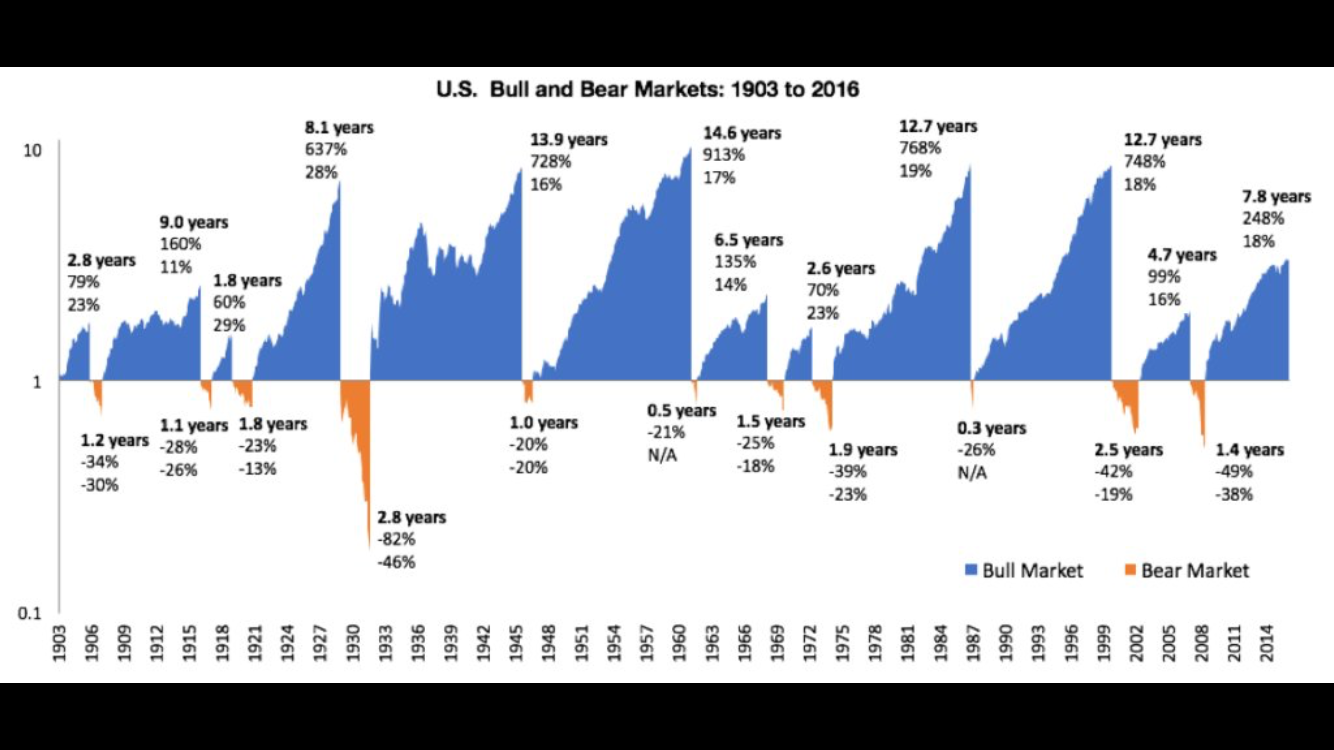

Hans dug up this graph. The bear markets since 1903 are in orange, the bull markets are in blue. Take a look at 1975 to the year 2000: we had a bear market for 4 months.

(Graph Credit: www.ftportfolios.com/Common/ContentFileLoader.aspx?ContentGUID=4ecfa978-d0bb-4924-92c8-628ff9bfe12d)

Why, given the long and compelling case to the opposite, do so many people bet against this? It falls into the category of behavioral error in investing, and it is powerful psychologically. What happens is that people blend their thoughts on something else that they feel emotional about with their investment outlook (like politics). This is often reinforced by a pessimist in the media who "sounds smart." The human mind is not good at strict compartmentalizing, and starts to bleed these thoughts together.

The error is compounded by the perception that they have some insight others do not, and that they will be able to predict markets and enhance their future with this insight, like selling out before a market crash or timing a buy at the bottom. These are common errors. This is called market timing.

There is no academic research I have ever found that shows that market timing works reliably. It is complete fiction that the financial media use to generate interest, and has lost American investors gargantuan sums of money. Burton Malkiel at Princeton lit up the literary world with his colorful conclusion on page 5 of his 2003 paper: "Moreover, the evidence is overwhelming that whatever anomalous behavior of stock prices may exist, it does not create a portfolio trading opportunity that enables investors to earn extraordinary risk adjusted returns."2

Let me use a real-world example of what you are up against if you try to time markets. Computer scientists at hedge funds now locate servers right near the buildings that house the Food & Drug Administration's servers. They scan every document in real time, looking for the government to change a word somewhere in a document that has meaning. Natural language processors "read" the words and determine the impact on stocks, and trade the markets, all within a fraction of a second. Sophisticated algorithms mix many more inputs into the decision. This has gone well beyond "having a hunch."

One Day In July portfolios lean heavily toward optimism, with exceptions made at the direction of clients or specific situations. And we don't engage in market timing.

Dan Cunningham

1. https://www.fool.com/investing/general/2016/01/21/why-does-pessimism-sound-so-smart.aspx

2. https://www.princeton.edu/~ceps/workingpapers/91malkiel.pdf